Zambada’s admission represents a seismic victory for US law enforcement in dismantling one of the world’s most violent and sophisticated drug empires. With a mandatory life sentence pending on January 13, 2026, and a staggering $15 billion forfeiture, the criminal ledger is closed—but the reverberations through US-Mexico relations, cartel dynamics and the lives seized by addiction and violence are just beginning to be reckoned with.

“His guilty plea proves no cartel boss is beyond the reach of justice.”

El Mayo’s rise through the Sinaloa cartel was marked by quiet dominance. While his partner Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán courted headlines, Zambada orchestrated trafficking webs with ruthless efficiency. Beginning in 1969, at age 19, he planted his first marijuana crop before evolving into a narco-baron responsible for moving at least 1.5 million kilograms of cocaine—and thousands of kilos of fentanyl, heroin and methamphetamine—into the US, earning hundreds of millions annually.

Behind the scenes, official graft fueled his ascent. Zambada openly acknowledged in court: “The organization I led promoted corruption in my home country by paying police, military commanders and politicians that would allow us to operate freely.”

He admitted directing subcontracted gunmen to kill rivals, conceding, “many innocent people also died”—a rare, unvarnished nod to the human cost of cartel power. According to court documents, federal prosecutors contend he ordered his own nephew’s killing for attempting to collect debts without his say-so.

Zambada’s capture in July 2024 unfolded like a narco thriller: He was lured onto a private plane by El Chapo’s son, Joaquín Guzmán López, and landed near El Paso, where US agents arrested him. That moment triggered a brutal power struggle—Sinaloa erupted into factional warfare between “Los Mayos” (Zambada loyalists) and “Los Chapitos.”

In court, Zambada appeared frail—gray-haired, slouched, clad in blue-over-orange prison attire. He spoke through a Spanish interpreter, reading from prepared remarks: “I recognize the great harm that illegal drugs have done to the people of the United States and Mexico and elsewhere,” he said, adding: “I take responsibility for my role in all of it and I apologize to everyone who has suffered or been affected by my actions.”

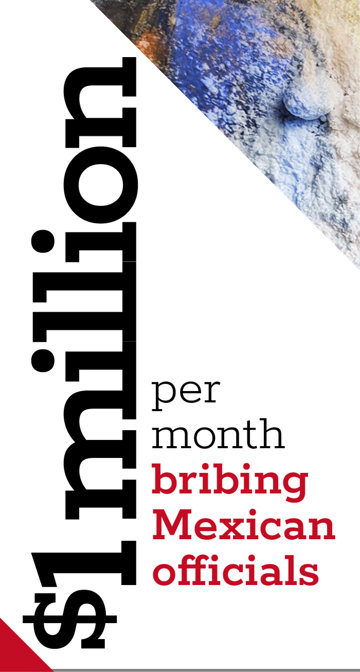

Zambada’s wife and all eight children—four sons and four daughters—were, at various times, tied to cartel logistics. In 2019, his son, Vicente Zambada Niebla, testified that his father set aside as much as $1 million a month for bribes to numerous high-ranking Mexican officials.

US officials hailed the plea. Attorney General Pam Bondi called it a “landmark victory,” labeling Zambada “one of the most prolific and powerful drug traffickers in this world”—a “foreign terrorist [who] committed horrific crimes against the American people.”

DEA Administrator Terrance Cole captured the moment—the gavel-heavy pageantry of the courtroom, the full freight of the US legal system bearing down: “His guilty plea proves no cartel boss is beyond the reach of justice. By taking him down, we are protecting American families and cutting off a pipeline of poison.”

US Attorney Joseph Nocella of the Eastern District of New York described the charges against Zambada as the culmination of joint investigations linking him to trafficking, murders and money laundering stretching back decades across multiple jurisdictions.

Facing death’s shadow and endless days behind bars, Zambada’s admission rings as both closure and a catalyst. Will a new truth—indeed, a new chapter in America’s decades-old war on drugs—emerge?

Mexico’s elite—governors, generals and political insiders—may soon find themselves under scrutiny.

The man who once poisoned streets and bought impunity has opened a dangerous portal into the darkest corridors of power. As Sinaloa bleeds from civil war and US courts prepare Zambada’s final judgment in the coming months, the question lingers: Who else will go down with him?